I’ve talked about how the drug czar is trying to cover up the failures of supply side drug war (and all the other aspects of the national drug control policy) by simply saying the word “balance” as much as possible. “It’s a balanced approach,” they say, and that’s somehow supposed to make us go “Oh, well, then, that must be OK. I thought we were spending $15 billion on failed policy. I didn’t know it was balanced.”

Expect to hear this mantra over and over again. From President Obama

Speaking to reporters yesterday afternoon in the White House Rose Garden, Presidents Obama and Calderon stressed the unwavering partnership between the two nations. […] the President highlighted the Strategy’s important balance of enforcement, prevention, and treatment.

Or from Secretary Kathleen Sebelius, Department of Health and Human Services

One key health objective in this new blueprint is to prevent and treat substance abuse before it becomes life-threatening, and the strategy we unveiled last week calls for a balance of prevention, treatment and law enforcement to accomplish our collective goals.

I was talking to my friend George a week ago about this, but he thought the whole “balance” concept was great and decided to implement it at the restaurant where he worked.

I saw George again earlier this evening and asked how his experiment was going.

“Well, first I told my boss that I was starting a new program that would put valuable balance into my work,” George said. “And then I struck a balance between selling food to customers, testing the quality of our food to insure customer satisfaction, and mentally preparing for future customers so they get the attention they deserve.”

I asked George how that went over.

“I was quite pleased with it,” he replied, “but for some reason my boss wasn’t. After just one week, he confronted me and said ‘So far all I see of your balance is that you’re eating more food than you’re selling and you’re taking twice as much time on break as you are working.’

Clearly he didn’t get it, so I explained to him that it was unfair to micromanage the specific aspects — that the important thing was that it was a balanced approach.”

George is now taking a balanced approach to job hunting.

Of course, the Drug Czar won’t lose his job, despite the fact that his “balanced” approach is actually destructive.

Here’s just one of many examples:

Creating New Soldiers in Mexico’s Drug War: How U.S. drug policy is making Mexican cartels more deadly by Marcelo Bergman for Foreign Policy Magazine.

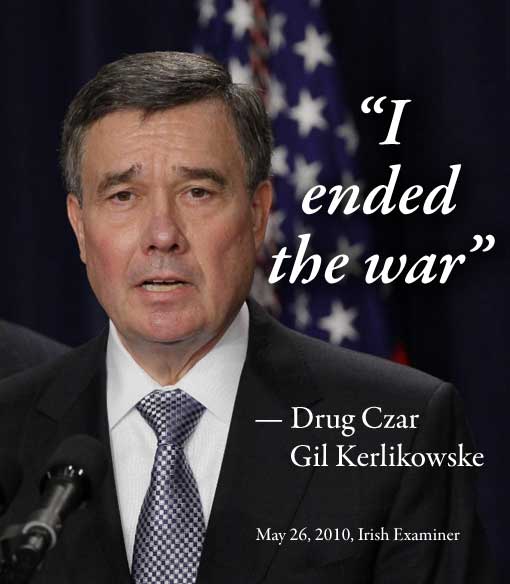

Barack Obama’s drug czar, Gil Kerlikowske, once said that he wanted to retire the phrase “war on drugs.” But on the U.S.-Mexico border, where the drug war is less metaphorical, the United States remains an enthusiastic ally — and the Obama administration has gone to great lengths to show it.

Yes, we know that supply-side doesn’t work, but it’s OK, it’s part of a balanced effort, so we’re going to continue spending money on it like crazy.

The more than $50 billion it has spent on interdiction efforts over the past quarter-century have barely made a dent in this demand.

The efforts have, however, altered the structure of the drug trade. The production of marijuana and heroin in Mexico through the 1960s and 1970s was the province of small-time operators, many of them family-type organizations, which could move drugs across a laxly policed U.S.-Mexico border without much risk of capture. […]

As the United States stepped up its enforcement efforts at key transshipment points — the Caribbean and the U.S.-Mexico border — and paid its Latin American drug war allies to do the same elsewhere, moving product into the United States became more difficult. Traffickers today must outwit American soldiers, Drug Enforcement Administration agents, and Border Patrol officers. […]

None of this has slowed the drug trade — demand, remember, has remained mostly constant. Instead, the cost of getting into the business has risen. To escape stringent enforcement, today’s smugglers need deep pockets to run the sophisticated logistics needed to escape detection and seizure, pay the necessary bribes, and absorb substantial losses of their product when seizures do happen. These barriers to entry have winnowed the trafficking business down to a handful of major players: first Colombia’s MedellÃn and Cali cartels in the 1980s and 1990s, and now the five key Mexican cartels. Smaller outfits, meanwhile, have found new, less daunting lines of work as suppliers and service providers for large syndicates. […]

As a result, a business that once enjoyed a certain degree of market competition is now an oligopoly. […]

As the cartels have shrunk in number, the pressure on them — from U.S. and Mexican authorities, and from their own competitors — has increased apace, forcing the organizations to become better equipped and more violent. Today’s Mexican cartels spend millions of dollars a year on assault rifles, explosives, armored high-end SUVs, and sophisticated intelligence operations, with the aim of avoiding interdiction and eliminating competitors.

This is the grand paradox of drug enforcement. Unless enforcement agencies can intercept virtually all of the drugs crossing the border — something that approaches impossibility — their efforts are likely to simply produce more formidable opponents.

But at least it’s a balanced approach.

Negroponte, a former U.S. ambassador to Mexico who has been working on drug control for 35 years, urged legislators to not be discouraged by the increased violence or drug availability.